We finished part 1 leaving our readers wondering what the City of London has to do with 1871. Mayer Amschel Rothschild once said, “Give me control of a nation’s money supply, and I care not who makes its laws”. This #PrussiaGate series will focus on the invisible players seeking to control a nation by controlling the issuance of its money and credit. Those who wish to conquer nations are not interested in its laws, but instead its money. Therefore, the ‘District of Columbia Organic Act of 1871’ is not of great relevance to this series. However, the ‘Treaty of Washington 1871’ is another matter entirely. We will be following the money, and trying to expose the invisible army that controls nations.

Part 1 revealed how the City of London came into being. Founded by the Romans in 47 A.D., it quickly became a valuable trading post for the Roman Empire. Today, many ancient Roman temples have been discovered within the Square, particularly on “Temple St”, which is testament to its religious history. The City’s name also bears the echo of its cultural lineage:

From its earlies beginnings, Londinium has maintained its status as one of the world’s most significant trade-centers. Today, it is now known as The City of London Corporation. Incredibly, the nickname for the council of twelve members of the corporation is ‘The Crown’.

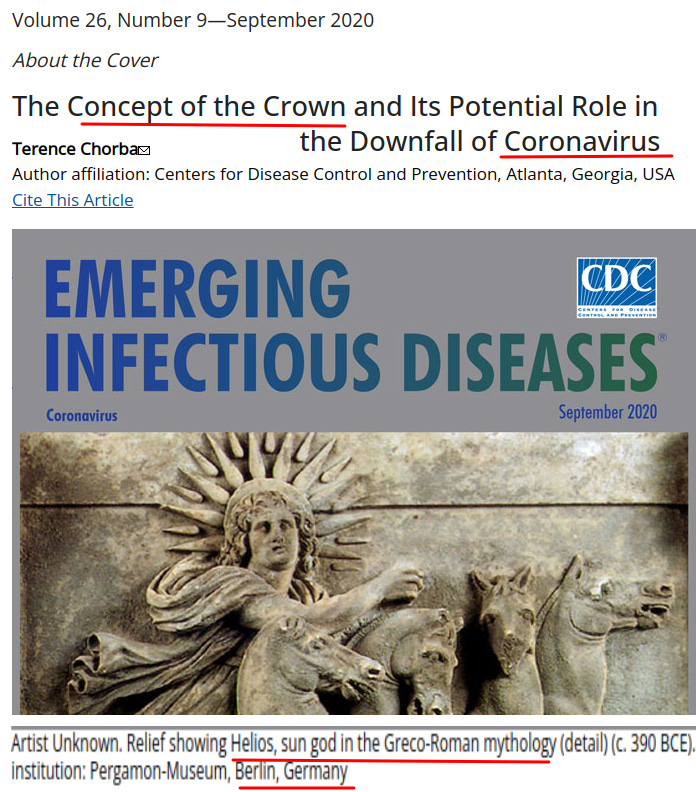

Considering the last few years of plandemic hysteria, the correlation between the Roman heritage of the City of London, the Crown and the coronavirus that kick started global lockdowns is certainly interesting. Even more interesting was the CDC’s September 2020 publication regarding the coronavirus, particularly their interest in ancient Roman gods:

As you can imagine, all this ancient Roman symbolism is opening another can of #PrussiaGate worms. One day we will return to look at this through a #PrussiaGate lens, but for the time being we are focused on the “horrible invisible enemy”, the “oranges of the investigation”, and how it all relates to the Treaty of 1871.

This article will present how the City of London Corporation (aka The Crown, and “Invisible Empire”) amassed enormous wealth by pillaging America. We will show that those travelling to America in search of a better life were forced to use paper money, but required to pay back their loans in physical gold and silver. In this manner, the trade and productivity of hard-working Americans were rewarded with worthless paper, while the vaults in the City of London were bursting with bullion. The final nail in the American coffin arrived in 1871, and ensured a never-ending stream of shiny precious metal back to The Crown.

Before we reveal how this was accomplished, there are two foundational concepts that must first be understood.

Gresham’s Law

Put simply, if a nation is forced to use a “shit-coin” to trade goods and services, the shit-coin will eventually drive out the other currencies used for exchange.

A currency that is of no worth to any other nation will not be used anywhere else. Therefore, when that nation imports things from another country, they must pay for it with money that is accepted for world trade. Conversely, when that same nation exportstheir goods overseas, they will receive their own shit-coin back as payment.

In this way, all the “good money” will eventually be replaced by the “bad money” that has been forced upon the people. This worthless paper-money is referred to as fiatcurrency; a word which also has its root in Latin:

For millennia, the highest echelons of international trade and finance considered gold and silver as the best forms of money. This is why one-fifth of the world’s current gold supply is still sitting in the vaults underneath the Bank of England and in other vaults across the City of London. Anyone who tries to convince you otherwise is trying to take your gold, and will demand you accept fiat as legal tender.

This is an important concept to grasp, because from the 1600s, European powers embarked on a rapid expansion of their colonial empires. Colonial expansion served European powers and their systems of mercantilism:

Understanding the connection between Mercantilism and Gresham’s Law is critical. These two systems worked together to ensure that bullion streamed into the City of London like a champagne fountain at a Great Gatsby party.

Once the immense natural wealth of America was discovered, the banksters decided it was time to ‘Gresham the living-daylights’ out of this rich continent, and then sit back and watch the river of bullion flow.

Bringing the Receipts

As #PrussiaGate readers are aware, we use open-source for all our references. In this Part, there are three books which have provided incredible detail and insight into the financial chicanery that occurred in America for centuries. The hard work has been carried out by these authors who have gone to enormous efforts to ascertain the real numbers behind the American economy during the 18th and 19th centuries:

For those who want a greater insight into what transpired over recent centuries, these books are highly-recommended reading.

The details within the #PrussiaGate story of 1871 would not be possible without the work of these brilliant authors.

1690 – The Colonial Alchemists

In the early days of the American colonies, the British pound was used as money. Back in those days, the pound was based on 86 Troy grains of silver. There was also the gold Guinea, which was 129.4 grains of gold. The money used by the British was hard-currency, backed by either gold or silver, which are otherwise known as “specie”.

During the colonial days, British money was scarce. Settlers in the American colonies found other ways to trade. Beaver fur, wampum, fish and corn were items used to trade with Indians in the North. Rice was used in South Carolina, and tobacco was used as a hard-currency in Virginia.

For a fledgling nation with very little gold or silver in circulation, these forms of money are acceptable mediums of exchange. However, as the American economy developed, the Europeans wanted more and more of what it was producing. This emerging demand meant that European money, which was backed by gold and silver, was trying to make its way to America. However, if this happened, Europe would see a net flow of bullion out of their vaults, and into US vaults. This scenario was the antithesis to their mercantilist practices. The powers within the City of London regarded this as an utterly unacceptable predicament.

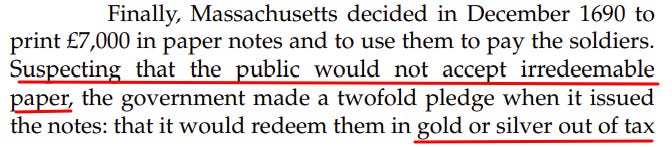

As we have presented, William III of Orange took the English throne in 1688. Incredibly, within just two years of his reign, the monetary systems of the American colonies were “reset”, starting with Massachusetts:

Massachusetts had just been issued with one of the world’s first “shit-coins”. Predictably, nobody believed that the paper was worth the same as gold and silver, and so the price of the paper-notes began to plummet:

When the Governor of Massachusetts decreed that paper-money was legal tender, and it could be used to pay “all debts at par with specie”, he had turned the paper into a fiatcurrency.

The force applied by the government against the free market was violent. If citizens did not accept the money, they could be fined, imprisoned or have their property confiscated. Furthermore, the government continued to print more and more paper-money, which resulted in massive price rises for the average person. This action meant that something else happened in the Massachusetts economy:

The paper money flooding into Massachusetts resulted in an inflationary boom, followed by a deflationary depression

. The average person suffered immensely during this time, but it created a windfall for the international merchants and bankers.

Massachusetts had to pay for all imported goods in specie because the international traders did not accept the worthless colonial paper. However, their exports to international traders could be settled with worthless paper-money, which had been made compulsory legal tender in Massachusetts.

When the value of the fiat currency dropped to over 10-to-1 versus gold and silver, a massive arbitrage developed that could only benefit those with connections to the City of London.

As an example, a wealthy London merchant could theoretically do the following:

- Travel to Massachusetts and swap gold for heavily devalued “legal tender”. The amount of gold that was promised on the Massachusetts paper-money was 10 times more than the actual gold that he swapped.

- Go to the docks and purchase a commodity such as tobacco, and force the seller to accept the paper-money as payment. This meant that the amount of tobacco the London merchant could buy was 10 times more than if he tried to purchase it with an actual gold coin. If the seller refused to accept the paper money as an equivalency to gold, the merchant could inform the authorities and have the goods confiscated altogether.

- The London merchant would then ship the tobacco back to the City of London, where it is traded on the London Commodities Exchange at fair value, and denominated in gold-backed money.

- Assuming prices remained stable, the London merchant ended up with 10 times more gold than he started with back in Massachusetts.

- The merchant would then go back to America. Rinse. Repeat.

This was akin to alchemy: The value of the goods from America were exchanged in the City of London for gold-backed money, while the original seller received fiat currency. Let’s consider the entities that the London merchant needed to use in order to carry out this massive arbitrage:

- Gold (or silver) which would most likely be transported from London or organized by subsidiary banks in America.

- An FX dealer to provide the heavily discounted colonial paper currency.

- Lloyds of London to insure the cargo from America to London.

- The Baltic Exchange to facilitate the physical shipping of the tobacco to London.

- London Commodities Exchange to facilitate the sale of the tobacco.

- London private banks to arrange for receipt of money.

- London Bullion Exchange to convert British pounds back into physical gold or silver bullion.

All these entities sat neatly within the walls of the City of London, and commissions were charged for every transaction. Everyone made a handsome profit from the trade, except for the American colonialists on the other side of the pond. They were stuck with worthless paper, while trying to survive within a never-ending cycle of inflation, deflation, and poverty. It was a cruel form of uber-mercantilism, and it was pissing off the colonials, big time.

The Sparks of Revolution

The disaster in Massachusetts illustrates the complete failure of fiat currency. However, since it filled the City’s vaults with bullion, every other colony adopted similar monetary systems. The result: every colonial subject was now receiving pennies on the dollar for their labor, goods and capital. No one avoided the catastrophic consequences:

From 1690 to 1750, this monetary policy in America left many destitute. It was a miserable situation because gold and silver were in very short supply, and what money they did have, continually reduced in value.

Things became so desperate that the British Parliament called for an immediate end to the use of fiat currency in the colonies, and a return to gold and silver as legal tender. From 1750-1764, prices stabilized, and America began to prosper

.This initiative meant that the bullion arbitrage disappeared for the City of London. Predictably, the merchants sought to find new ways to continue their mercantilist practices.

During the same period, King George III was embroiled in the nasty Seven Years Waragainst the French. Although victorious, he found himself in enormous debt to the money-lenders from the square-mile. From 1750-1764, the lost profits from the bullion arbitrage were replaced by profits from financing King George III’s war. When the war ended in 1763, the British king had to pay back his debt. He decided to tax the daylights out of American Patriots:

This excessive taxation was what ignited the tinder-box of liberty, and the American Revolution was underway. A disorganized nation and a rag-tag army led by George Washington took on the might of the British Empire. Consider, back in the day, the enormous odds the patriots faced. King George III and his team were supremely confident of victory, however they were unaware of the invisible forces that were pulling the strings in the shadows.

Divide Finance and Conquer

In Part 1 we showed how generational waves of German merchant and banking families migrated to London during the 18th Century, effectively taking over the City of London. We also described how Frederick the Great commanded the most powerful espionage network in Europe, and how he welcomed the most powerful Jewish banking families into his kingdom; the Itzigs and the Mendelssohns.

King George III was Frederick’s cousin. Frederick’s former field marshall, Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick, had direct access to the British royals, and was revered by Britain. There was even talk of him commanding the British forces during the Revolutionary War. While this did not come to fruition, he did send over 4000 of his own troops to fight against the US Patriots.

In short, it is highly likely that Frederick knew the exact state of his cousin’s finances, as well as the state of his military.

Officially, Prussia stayed neutral during the American Revolution, however one of Frederick’s former elite officers had joined Washington’s army:

Von Steuben played a significant role in Washington’s army, but would later prove that his loyalties still lay with Prussia.

In other words, while Frederick the Great officially stayed out of the American Revolution, he could count on his powerful espionage network to report intelligence back on every aspect of the battle. This, of course, included the banking network within the City of London.

When the Patriots declared their independence, they had very few resources from which to take on the mighty British. Without assistance, they may well have been annihilated. But, when it comes to war, one can always count on the City for a loan or two:

Consider that the City of London, just up the road from Buckingham Palace, financed the rebellion in the American colonies! If there was ever any proof of the power and autonomy of ‘The Crown’, this was it.

Why would the City of London lend money to the Patriots? If we think like a merchant banker, there are two reasons that come into view:

- Bolstering the Patriots would create a stronger resistance to the British King, who was already deeply indebted to the City. Funding the weaker side would ensure that the war would last longer, costing more for both sides, which the bankers were funding.

- If the Patriots were victorious, a new nation would be born, which could become a significant new client. The war debt would ensured that this nation would begin its life heavily indebted to the City’s money-lenders.

It truly was a case of “finance and conquer”. An important detail had to be secured; if the Patriots won, the loans made during the Revolutionary War would have to be paid back in full, with interest.

Monetary ‘Magick’

The American Revolution was a time of great upheaval. The signatories on the Declaration of Independence were acutely aware they were committing treason. This was a mad-scramble to defeat the British, and every Founding Father brought their own, unique skill-set to the table. There was no right or wrong at this time; there were just Patriots and Traitors.

Without a doubt, the one thing George Washington’s army lacked was money. For this, he relied heavily on one of America’s richest men at the time:

The only problem was that Morris did not simply pluck the money from thin air:

In Part 1 we noted that Antonio Isaac Suasso financed William of Orange’s invasion of England. He was a Jewish/ Dutch banker who remained in London after the Bank of England was established. He was also loyal to the king of Spain. Could it be that his family and their connections also financed the American Revolution?

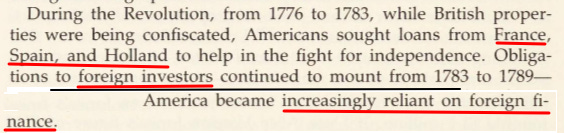

Whatever the case, the American foreign debt began to pile up, and they were wondering how they were ever going to be paid back. Many foreigners just assumed that the new American nation and its future abundance would become the collateral for their loans, and they could simply get back to business after the war:

Once the battle got underway, what little money the Patriots had was used to purchase weapons, artillery, and various other items. However, there was a much bigger problem looming. With so little “real money” available, how could Americans access money to live while the Revolution was underway? Congress resorted to the printing press:

Innovative measures were required, and so Congress issued debt that could also be used as currency; these were known as “loan certificates”.

The value of “loan certificates” were also collapsing because everyone knew that America could never pay back the debt, especially not in specie. The depreciated value of the certificates reflected this reality, until Robert Morris stepped in:

We must consider the enormity of Morris’ actions. These certificates were heavily discounted because no one thought they would get their money back.

Imagine the scenes in the City of London tea rooms after Morris’ announcement: Traders had bought these certificates at rock bottom prices; the federal government declares it will assume the debt AND pay back its full face value in specie (ie: gold and silver); significant fortunes were about to be made.

This scenario highlights how mercantilism and Gresham’s Law were both in play before the Republic even got off the ground. If the federal government assumed this debt, which they’d agreed to pay in specie, bullion would once again leave America and flow into the hands of those who owned the debt. The result on the ground was that Continental currency drove out hard-currency, again subjecting the nation to a shortage of gold and silver.

How on earth was Morris going to fulfill the promise to redeem these loan certificates in par?

Back in the 1600s, when William of Orange invaded England, he was predominantly financed by a wealthy Dutch financier. In the aftermath of the ‘Glorious Revolution’, the Bank of England was established. Fast-forward to the American Revolution: As the Dutch and Spanish were loaning money to American patriots, the Bank of North America was being established before the Republic had even been born. The timing of this is a notable coincidence.

Fortunately, Morris’ attempt to set up this Bank failed. “The first experiment with a central bank in the United States had ended.”

However, the nightmare had not ended; Morris’ protege would soon pick up from where he left off.

Hamilton’s Curse

The early days of the Republic were crazy times. The Union was hanging on by a thread, and there were furious debates about how the nation should be governed. The British had not given up their quest to destroy America; British agents were swarming everywhere, trying to break up the United States as quickly as possible.

Perhaps the fiercest political battle of the period was between Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton was a protege of Robert Morris, and was determined to institute a strong, centralized federal government with an equally powerful central bank. His vision included public debt that would be permanently financed through taxation. Jefferson’s philosophy could not have been more different:

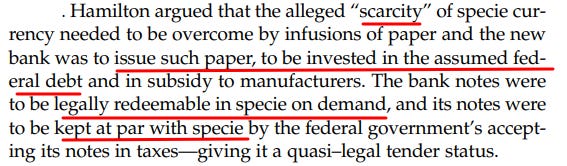

Initially, it was Hamilton who got the upper hand when he was appointed as President Washington’s Secretary of Treasury. His first order of business was to solve the disastrous state of the nation’s finances. As we mentioned previously, the use of fiat currency along with promising to pay back “loan certificates” at full face value had seen a massive disappearance of gold and silver from the national economy. What was Hamilton’s solution to this problem?

Hamilton resorted to creating yet another central bank, with paper-money to be used as legal tender. Gresham’s Law applied itself with force as fiat currency flooded the fledgling American economy, bringing the same predictable outcome:

When Alexander Hamilton received Congressional approval to establish The First Bank of the United States, he still needed to raise the required specie as initial capital. This was to be $2 million in gold and silver, and Americans were reluctant to give up their gold. Hamilton decided to look for money from the same place that William of Orange succeeded a century earlier:

Before the Constitution was even ratified, Hamilton was building some rather interesting relationships:

Hamilton succeeded where Morris had failed, and the bank’s printing presses were unleashed. As Americans suffered the predictable ravages of inflation, the shares in the Republic’s first central bank were gradually falling into the world’s wealthiest merchants and bankers, in the City of London:

Notably, it was the German-British Barings bank, known as the “Sixth Great Power” of Europe at the time, which became the primary broker for The First Bank of the United States.

If America did not have the likes of Thomas Jefferson and the ‘Jeffersonians’ viciously opposing Hamilton at every turn, the nation would have been plunged into a perpetual debt burden. Jefferson fought the bank tooth and nail:

When he became president, Jefferson worked tirelessly to reduce the public debt as quickly as possible. This process was certainly not a smooth one. Jefferson’s Vice President, Aaron Burr, killed Hamilton in a duel in 1804, and soon after, Jefferson outed Burr as a traitor, and he was tried accordingly. When the court found Burr ‘not guilty’, he fled to Britain.

These were crazy times, but nothing stopped Jefferson’s tunnel vision to destroy the Bank of the United States:

For a brief period, America was freed from the financial mayhem of Gresham’s Law and the grips of central banking. Such freedom was a repugnant situation for the bankers within the City of London; it was time for another War.

Jacksonian Balls of Steel

One year after the Jeffersonians defeated the Bank of the United States, war with Britain was raging again. When the War of 1812 kicked into gear, the same old problem presented itself; how the hell was America going to pay for it?

Bullion once again disappeared from the economy:

As soon as the war was finished, the same problem that emerged in 1791 appeared again, and the Congress voted for the same insane solution:

While the outcome was the same, this time, there was a twist. The newly printed money did not just increase consumer prices, it also increased asset prices. Many tried to make money by speculating on the prices of everything; wheat, real estate, and even slaves. While there were some good times, the bad times arrived pretty quickly:

This was a total disaster. Unaware of the financial machinations operating in the shadows, average people were blind to the reality they were being “pumped and dumped”. The inflationary boom brought on by a reckless credit-expansion gave people a sense of prosperity; they were pumped! As gold and silver disappeared from circulation, the boom turned into a terrible depression which resulted in crashing prices, bankruptcies and poverty; they were dumped!

There was a silver lining from these repeated monetary crises, and the intense hardship they wreaked upon the citizenry. It inspired Andrew Jackson to destroy the grasp the bankers had on America’s sovereignty.

This movement was going to hit the City of London bankers right where it hurt them the most; in their bullion vaults. Removing America from the power of the printing press of The Second Bank of the United States would not be easy. However, the Jacksonians had hard-money balls!

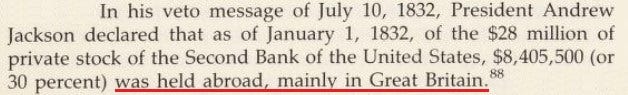

In 1832, Jackson vetoed the recharter of the Second Bank of the United States. However, there was a detail in his speech that is often overlooked:

Once again, the shares of America’s central bank were being gradually accumulated in Britain, and most likely traded on the London Stock Exchange, in the City of London.

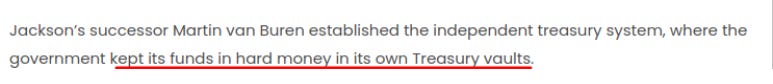

President Jackson was having no more of this bullshit. In 1833, he withdrew all the federal government’s deposits from the bank, immediately destroying its ability to operate:

The Golden Years

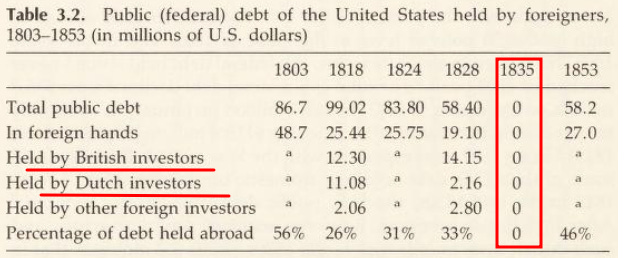

For a moment in time, America was debt free, had no central bank, and was on a hard-currency standard:

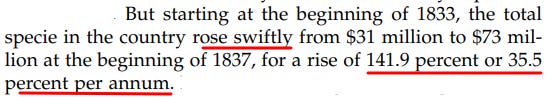

America was a young nation with enormous natural wealth; its citizens had just been launched into “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness”. This was the first time the world could see the potential economic powerhouse that was America:

As soon as America began trading with hard-currency, they levelled the playing field with their European counterparts. The effect was immediate, and bullion from all over the world poured into America.

This did not please the City of London at all, and a counter strike was imminent. 1837 saw the arrival of a nasty global depression:

The City of London was not just worried about the flow of gold out of London; they were also worried about their American loan-book:

For the next 20 or so years, America was trading without a central bank. But behind the scenes, London was quietly accumulating assets in America:

The rising economic power of the United States was a direct threat to the City of London. When the time was right, they would be ready to strike. To stop this emerging juggernaut, London would need a war, war finance, paper money, debt, and ultimately, a central bank.

Their opportunity arrived with the American Civil War; it was the Mack Daddy of all financial opportunities.

Cutting to the Chase

Wars cost money; big money. Without going into the “whys and wherefores” of the American Civil War, at the end of the day it’s where the money came from in the first place that allowed the weapons and ammo to be purchased.

The Confederates were the clear underdog, but when the first shots were fired, European exchanges began to place their bets:

“London and Frankfurt” is a generalization for the “Barings, Ruckers, Schroeders, Rothschilds, Warburgs, etc..”, and they were based in the City of London.

How would these trading houses make vast fortunes? Put simply, they would lend to the Confederates, but restrict their lending to the Union. However, the Union also needed to find a way to fund their army.

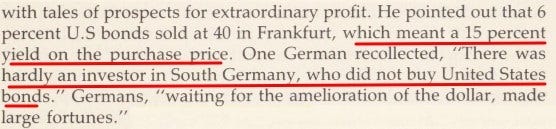

When the Union tried to sell bonds in Europe, very few people were interested in buying them, especially in the City of London. The lack of buying forced the price of Union bonds to collapse. When they reached a ridiculously low price, trading houses in Europe began to accumulate the bonds. At such huge discounts, the investment provided returns of around 15% per annum, redeemable in gold and silver. If successful, the payoff would be enormous, and ‘vast fortunes’ would be made.

The Confederates were effectively receiving foreign capital, which in turn allowed them to equip their army with enough firepower to adequately match Union forces. Conversely, the Union was somewhat cut-off from foreign finance, and rapidly began to run out of money during the war. By financing the underdog, the struggle between the North and South would become much more even and resulted in a much longer and costlier war.

This was a terrible situation that Lincoln and his Secretary of Treasury, Salmon P. Chase, were facing. The fate of the Republic was in the balance, and the tide was rapidly turning against it. Nobody was interested in buying US government bonds, and the hard-currency needed to pay for the war was in very short supply. How could they raise money and expedite the end the war?

Gresham’s Chase

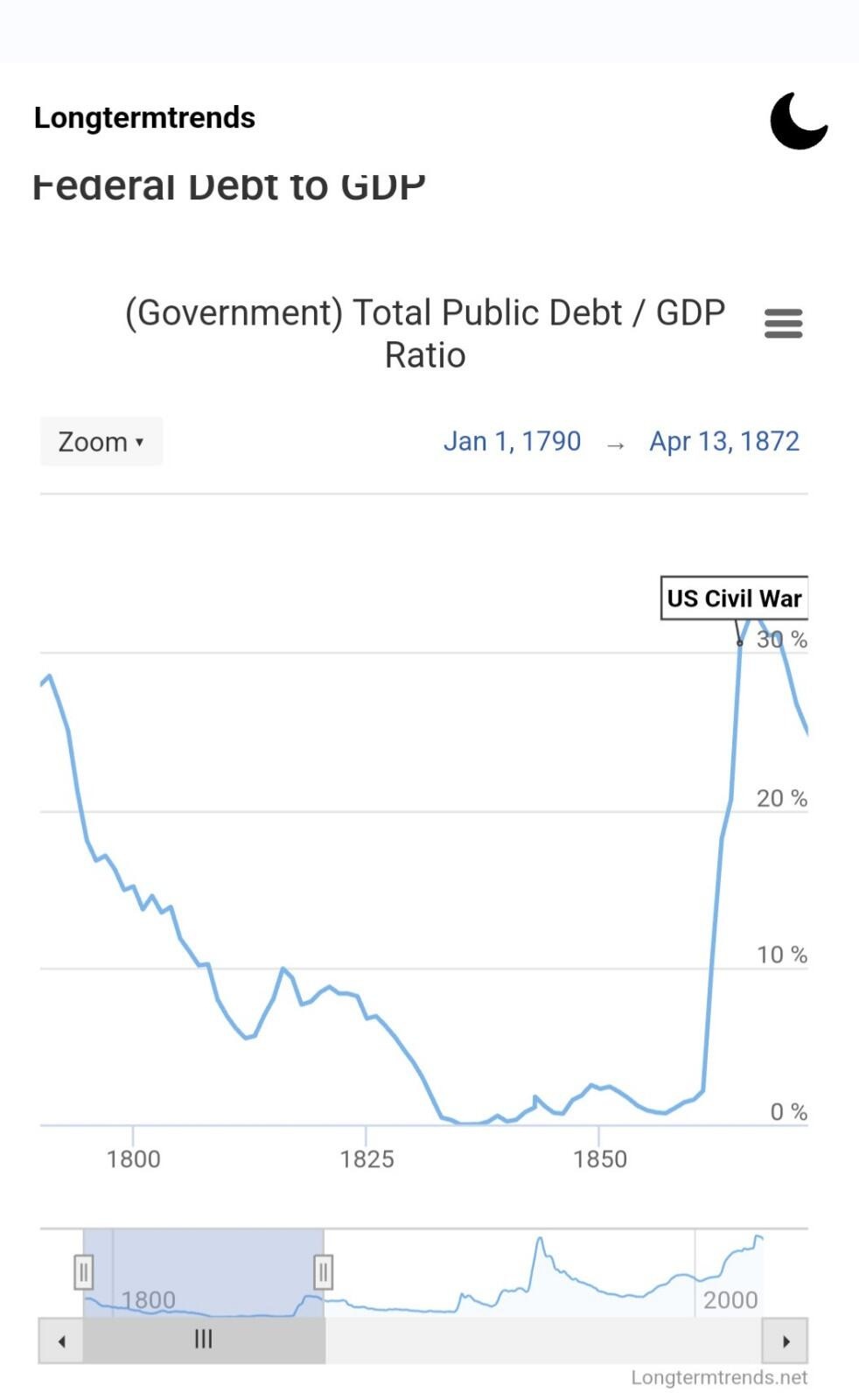

The financial cost of the Civil War was staggering:

Salmon P. Chase was considered a Jacksonian, which is strange when we look at what transpired under his watch. The first thing Chase did was to issue $150 million in bonds, that were bought by the nation’s banks. The problem was that Chase wanted the banks to pay for the bonds in specie, but none of them had enough precious metals in their vaults. At the same time, Americans smelled a rat, and started taking their gold deposits out of the banks.

Recall in Part 1, we showed how Charles I confiscated the gold from the Royal Mint and called it a “forced loan”. While not quite so obvious, Chase had done something similar. He was trying to get banks to buy his bonds with specie, and in return, the bond promised to pay back that gold later, with interest.

The real problem was that Chase had started a gold run on the banks. People wanted their specie well clear of any financial chicanery, regardless of the war. Chase knew exactly what was unfolding, and within no time the government moved to hold onto their gold, while trying to grab everyone else’s. The chase was on:

The Legal Tender Act sent Americans back to the colonial era. Greenbacks were no different from the Massachusetts fiat currency of 1690.

The worst part of the Legal Tender Act was that Treasury promised to pay its public debt in specie. By forcing the people onto the greenback and repaying government debts with gold and silver, a massive arbitrage trade emerged.

A savvy merchant-banker could sell greenbacks, which were forced upon the people, and in turn buy gold, silver or heavily discounted federal bonds which promised to pay back in specie, with massive interest. The more greenbacks that were in circulation, the greater the potential profit:

As greenbacks dropped in value, the trade was exposed for everyone to see. Chase panicked and tried to ban all gold trade, and then blamed “speculators” for the bullion that was literally pissing out of the Treasury vaults that Presidents Jackson and Van Buren had worked so hard to establish.

Nothing could stop the plummeting greenback. Chase was behaving like a desperate king doing desperate things. He tried to ban the gold market completely, before doing the unthinkable:

Just like that, Gresham’s Law had cast judgement on Salmon P. Chase. The Treasury was being emptied of its gold (hard-money) and getting replaced with the greenback.

When it came to the nation’s silver, a more-tragic story unfolded:

When the Civil War ended, the bodies of 600,000 men lay strewn across the country. Grieving families had to find a way to get on with their lives, but further pain lay dead ahead.

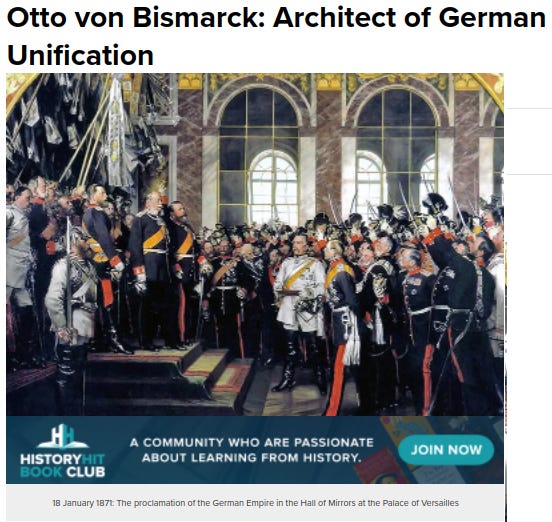

The Great Payback

When all was said and done, the war was over; Lincoln was assassinated; and Salmon P. Chase was ousted from office. For the average person, the value of the greenback evaporated their purchasing power, and inflation was running above 20% p.a. However, a much more ominous picture was unfolding for the Government. Chase’s attempt to prop up the value of the greenback saw the Treasury’s bullion inventory obliterated, and the public debt was out of control.

During the Civil War, the original investors of these US government bonds were predominantly Americans and American banks. To get on with life after the war, Americans needed money to rebuild, and many had to sell assets. For some, this included selling their heavily depreciated Federal government bonds for pennies on the dollar.

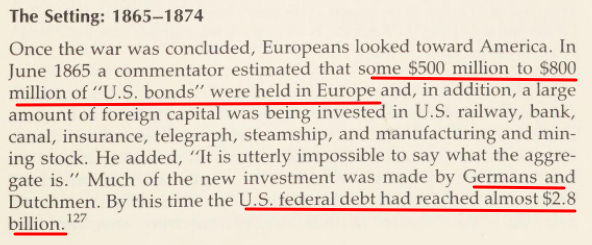

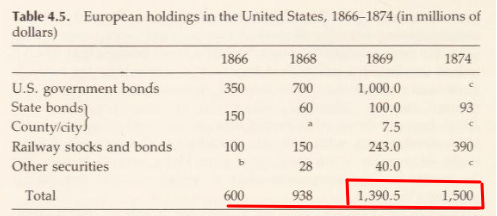

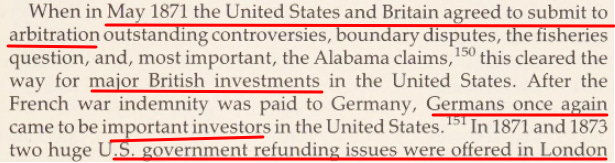

All of a sudden, Europeans were interested in buying American debt again:

Did somebody say “Germans”?

Prussian Private Banking

After the Civil War, Europe was developing an insatiable appetite for everything American, and this interest was predominantly being driven by German investors.

During the 1860s, Prussia was embarking on a brutal military campaign of its own against Denmark, Austria-Hungary and France; this was known as the German Unification Wars. In 1871, the king of Prussia was crowned the Kaiser of the German Reich.

In contrast to the financial desperation Americans experienced during the Civil War, Prussia appeared to be flush with cash. Their money needed to find a good place to invest, and following the civil war, America was ripe for the picking.

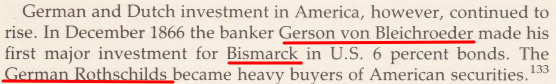

The Iron Chancellor himself invested a significant portion of his portfolio into the discounted American bonds, which promised to repay in gold, with interest:

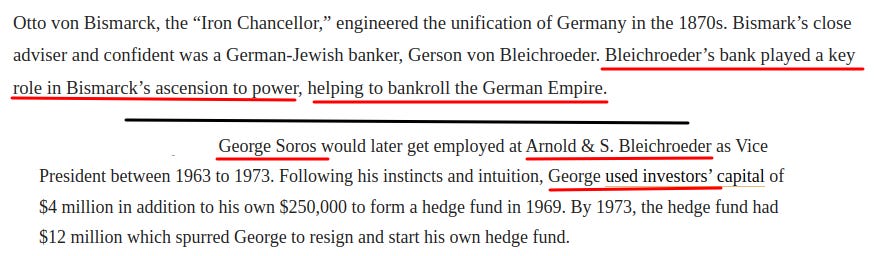

Bleichroder became a private banking powerhouse in the 19th Century, and his firm left an everlasting legacy on the world:

We cannot thank Bleichroder’s firm enough for getting George Soros’ career underway. However, what is the important point here is that Bleichroder was bankrolling the new German Reich, and encouraging Germans from all over the empire to buy heavily discounted US Government bonds. Bismarck led the way, and in no time at all, the German demand for America’s public debt skyrocketed.

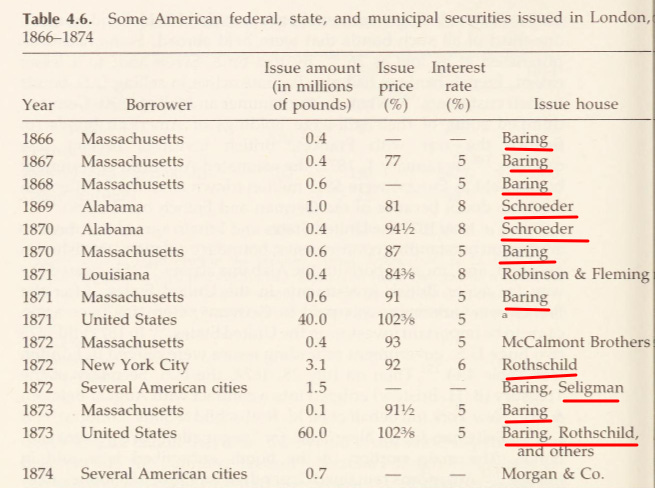

To understand how this happened, we can look to the German-British banks which issued the securities, in the City of London:

The same old question arose: How was America going to pay back its debts? After the Jacksonian movement, foreign bond holders were understandably worried about Americans giving the middle finger to the rest of the world, and potentially defaulting. After the civil war, America had very little gold and silver in circulation; the population was in a state of collective shock; and the average person had very little investment capital.

Would America ever be able to pay its dues to the bankers and brokers in the City of London, and to the hard-nosed investors within the German Reich?

From the investor’s perspective, it was time for Americans to get back to work, and repay their national debt. The last thing the bankers needed was for the US to enter another war; the next war may very well bankrupt the nation completely. Bismarck and Bleichroder were smart operators, and they knew what was required. America needed a certain ‘Prussian Providence’ that would allow the nation to mobilize and grow into its true potential.

Since the British and America had been bitter rivals since 1776, now was the perfect time for a good old fashioned Treaty:

Notice carefully that the government bonds were issued in London, under the jurisdiction of the City, or Roman London.

Also note, that the May 1871 agreement between the United States and Britain, is known as the The Treaty of Washington. It was the only treaty signed by America in 1871.

President Ulysses S. Grant signed the treaty, alongside other notable American politicians of the day.

As we’ve become accustomed, the devil, of course, is in the detail:

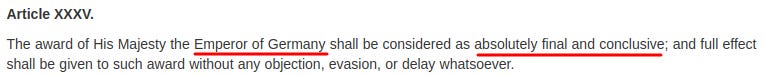

Let’s take a moment to consider what had taken place here: Prussia fought a series of wars during the 1860s; Wilhelm I, from the House of Hohenzollern and the prince of Orange, was crowned Emperor of the Germany Empire in January 1871; just a few months later in May, the Kaiser was appointed the final arbiter of a Treaty that not only forced Britain and America into peace, but also set a precedent that laid the foundations for the future of international law. No longer would the fate of a nation be decided by its citizens, but instead by an international court.

The short term result of the Treaty of Washington? Prussia and the City of London were going to get paid back, with interest and in gold, whether America liked it or not.

To be continued………………..

https://www.etymonline.com/word/corona

https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/26/9/ac-2609_article

https://www.investopedia.com/terms/g/greshams-law.asp

https://www.etymonline.com/word/fiat

https://www.wordnik.com/words/mercantilism

https://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674396661

https://mises.org/library/history-money-and-banking-united-states-colonial-era-world-war-ii

https://mises.org/library/hamiltons-curse

Rothbard, Murray N. A History of Money and Banking in the United States. Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2002. p 47

Rothbard, Murray N. A History of Money and Banking in the United States. Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2002. p 48

Rothbard, Murray N. A History of Money and Banking in the United States. Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2002. p 51

ibid. p 52

ibid. p 53

ibid. p 54

ibid. p 54

ibid. p56

https://www.theclassroom.com/taxes-did-king-george-impose-new-england-colonies-8316.html

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/baron-von-steuben-180963048/

Wilkins, Mira. The History of Foreign Investment in the United States to 1914. Harvard University Press, 2004. p 28.

Rothbard, Murray N. A History of Money and Banking in the United States. Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2002. p 61

ibid. p 62

ibid. p 61

ibid. p 62

ibid. p 63

ibid. p 68

ibid. p 69

Wilkins, Mira. The History of Foreign Investment in the United States to 1914. Harvard University Press, 2004. p 38.

https://www.ushistory.org/valleyforge/served/hamilton2.html

Wilkins, Mira. The History of Foreign Investment in the United States to 1914. Harvard University Press, 2004. p 39.

Rothbard, Murray N. A History of Money and Banking in the United States. Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2002. p 71.

ibid. p 73

ibid. p 76

ibid. p 82

Rothbard, Murray N. A History of Money and Banking in the United States. Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2002. p 90

ibid. p 90 – 91

https://www.newsweek.com/understanding-donald-trumps-obsession-andrew-jackson-592635

Wilkins, Mira. The History of Foreign Investment in the United States to 1914. Harvard University Press, 2004. p 61

Wilkins, Mira. The History of Foreign Investment in the United States to 1914. Harvard University Press, 2004. p 54

Rothbard, Murray N. A History of Money and Banking in the United States. Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2002. p 97

ibid. p 99

ibid. p 102

Wilkins, Mira. The History of Foreign Investment in the United States to 1914. Harvard University Press, 2004. p 101

ibid. p 102

ibid

ibid. p 103

Rothbard, Murray N. A History of Money and Banking in the United States. Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2002. p 122.

ibid. p 123

ibid. p 123

ibid. p 124

ibid. p 125

ibid. p 126

https://www.longtermtrends.net/us-debt-to-gdp/

Wilkins, Mira. The History of Foreign Investment in the United States to 1914. Harvard University Press, 2004. p 107

ibid

Wilkins, Mira. The History of Foreign Investment in the United States to 1914. Harvard University Press, 2004. p 107

https://whalewisdomalpha.com/bleichroeder-lp-new-hedge-fund-has-shown-big-winners/index.html

https://www.therichest.com/rich-powerful/heres-how-george-soros-became-a-self-made-billionaire/

Wilkins, Mira. The History of Foreign Investment in the United States to 1914. Harvard University Press, 2004. p 112

ibid

https://www.trans-lex.org/502000/_/treaty-between-the-united-states-and-great-britain-1871-/#head_26